By Sinclair Dinnen and Lincy Pedeverana

It’s been ten years since the publication of the Justice Delivered Locally (JDL) in Solomon Islands research, documenting justice experiences in rural communities across five of the country’s nine provinces.

A lot has changed in the intervening decade, including the ending of the 14-year-long RAMSI (Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands) intervention in 2017 and, more recently, Solomon Islands’ growing entanglement in the geopolitical tussle between China and the United States and its allies.

However, much remains largely the same, including the enduring challenges of governance and service delivery, and poor economic outlook confronting this Pacific Island nation.

A recent field trip to Malaita and Central provinces as part of an ongoing Australian Research Council Discovery Project investigating community rule-making in the Pacific Islands as regulatory innovation confirmed that not much has changed in how Solomon Islanders manage everyday disputes and safety.

The predominantly rural population (74% of an estimated population of 750,000) are still reliant on informal community-based approaches for settling disputes and managing personal safety.

Local justice practices tend to draw upon different, overlapping sources of authority, notably kastom, state and church.

Building the capacity and effectiveness of state policing and justice systems was a major component of RAMSI’s state-building engagement, and these efforts have continued on a reduced scale through bilateral assistance.

However, extending the reach of these services across the archipelago remains an ongoing challenge owing to geography, and fiscal and administrative constraints.

Most Solomon Islanders continue to depend on hybrid configurations of community-based actors – for example, chiefs, committees and churches – with whatever ‘bits of state’ are present or accessible in particular areas.

Despite the intense coverage devoted to China’s expanding influence, a more pressing concern for many Solomon Islanders is the growing fragility of social order at community levels.

This entails the destabilising impacts of disputes and stresses linked to socio-economic change, including problems associated with substance abuse, land disputes linked to logging, mining and development projects, and climate change.

Existing forms of community-based order maintenance struggle to manage newer kinds of disputation and discord, with traditional authority and leadership seriously weakened in many places.

Survey data indicates a strong desire among rural respondents for better access to state justice services, particularly the police, to manage growing threats to local social order.

Ongoing research into community rule-making indicates the prevalence of local order-making activities in many parts of the region, often in areas where the state has a limited or ineffectual presence.

An important purpose of this kind of activity is to improve local coping strategies in the face of mounting social order pressures.

The earlier JDL research, which the first author was involved with, noted extensive experimentation with community governance and regulation in rural settings, often entailing a proliferation of local committees and, in many places, the elaboration of detailed community by-laws.

Sinclair Dinnen and Lincy Pendeverana

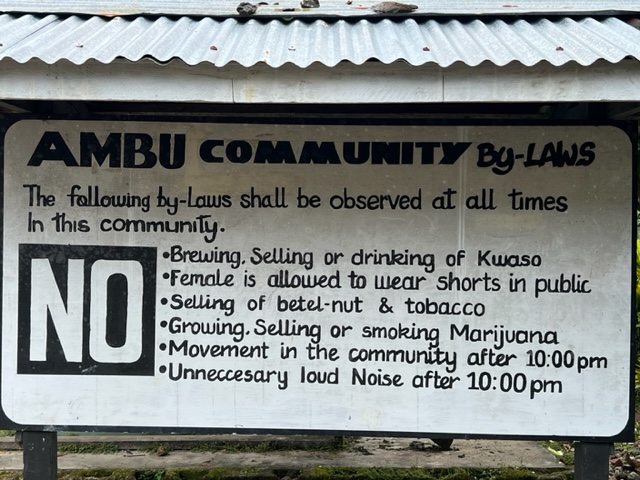

The latter are usually written down and displayed prominently on community notice boards, though having no legal status in the national justice system.

While their content varies, community by-laws are likely to include minor offences covered by the penal code, such as stealing and assault.

Other matters might relate to community safety, stability and health, such as prohibitions on kwaso (homebrew) and marijuana, noise and movement after certain hours, and rules around hygiene and community cleanliness.

Some prohibitions reflect cultural and faith-based beliefs, such as the banning of certain kinds of clothes for women (for example, cargo pants), and sometimes for young men (for example, loose trousers exposing underpants), and sanctions for disrespecting chiefs.

Prohibitions can also be directed at the perceived negative effects of technological change (for example, accessing pornography on phones), while others mirror national policies and campaigns aimed at changing social attitudes and behaviour (for example, domestic violence).

The diverse content of by-laws reflects the plural, changing and contested normative milieus in many local communities.

Community by-laws are also, in part, about forging more effective linkages with state agencies and, in particular, the police, given their strong powers of enforcement (something chiefs and other community leaders lack).

By adopting the form and, sometimes, the substance of state law, it is anticipated that external support will be forthcoming.

This is the shadow of the law effect. Such expectations have been encouraged by the police and NGOs in some areas, through crime prevention and community safety programs.

A major vulnerability with community by-laws – whether initiated organically or with external assistance – is that they ultimately depend on the police and other relevant bits of state (such as courts) being available when needed.

Failure in this regard risks undermining the efficacy of the by-laws and further eroding the authority of local leaders.

Community by-laws are one form of the wider experimentation in local order-making and community governance going on in Solomon Islands.

They signify active agency and resilience at local levels that often eludes the attention of commentators and decision-makers.

However, they also speak to growing stresses and social order challenges experienced at the most local levels that also rarely attract external interest, unlike disturbances in the national capital.

A key lesson from the recent tensions in Solomon Islands is that parochial local disputes can, if left unaddressed, rapidly escalate.

While primarily about strengthening local coping strategies, community by-laws and other order-making initiatives are also about fostering productive connections and relations with actors and institutions across different scales.

As such, they provide an important portal into broader processes of state formation in Solomon Islands, and serve to highlight the mutual dependence between community building and state building.

* This article appeared first on Devpolicy Blog (devpolicy.org), from the Development Policy Centre at The Australian National University. Sinclair Dinnen is an associate professor in the Department of Pacific Affairs, Australian National University. Lincy Pedeverana is a senior lecturer and Head of the Geography Department at Solomon Islands National University. He undertook his doctoral studies with the Department of Pacific Affairs at the ANU.

You must be logged in to post a comment.