When COVID-19 struck Solomon Islands in 2020, it sent shockwaves through an already fragile economy, cutting off trade, tourism, and jobs. In response, the Sogavare-led DCGA government turned to what it believed could drive a quick economic recovery: mining.

Key Points

– Siruka nickel mine approved under “fast-tracking policy,” sparking concerns of favoritism and weak governance.

– Environmental breaches threaten marine life and Waghena’s seaweed farms, with poor enforcement.

– Landowners report a lack of consultation, coercion, and unresolved ownership disputes.

– Communities see no royalties despite shipments; expired licenses and secrecy fuel mistrust and fears of corruption.

When the Democratic Coalition Government for Advancement (DCGA), led by then Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare, sought to cushion the economy from the pandemic’s fallout, it turned to the extractive sector. Central to this push was the “mining fast-tracking policy,” designed to accelerate select mining projects as a pathway to boost revenue and attract investment.

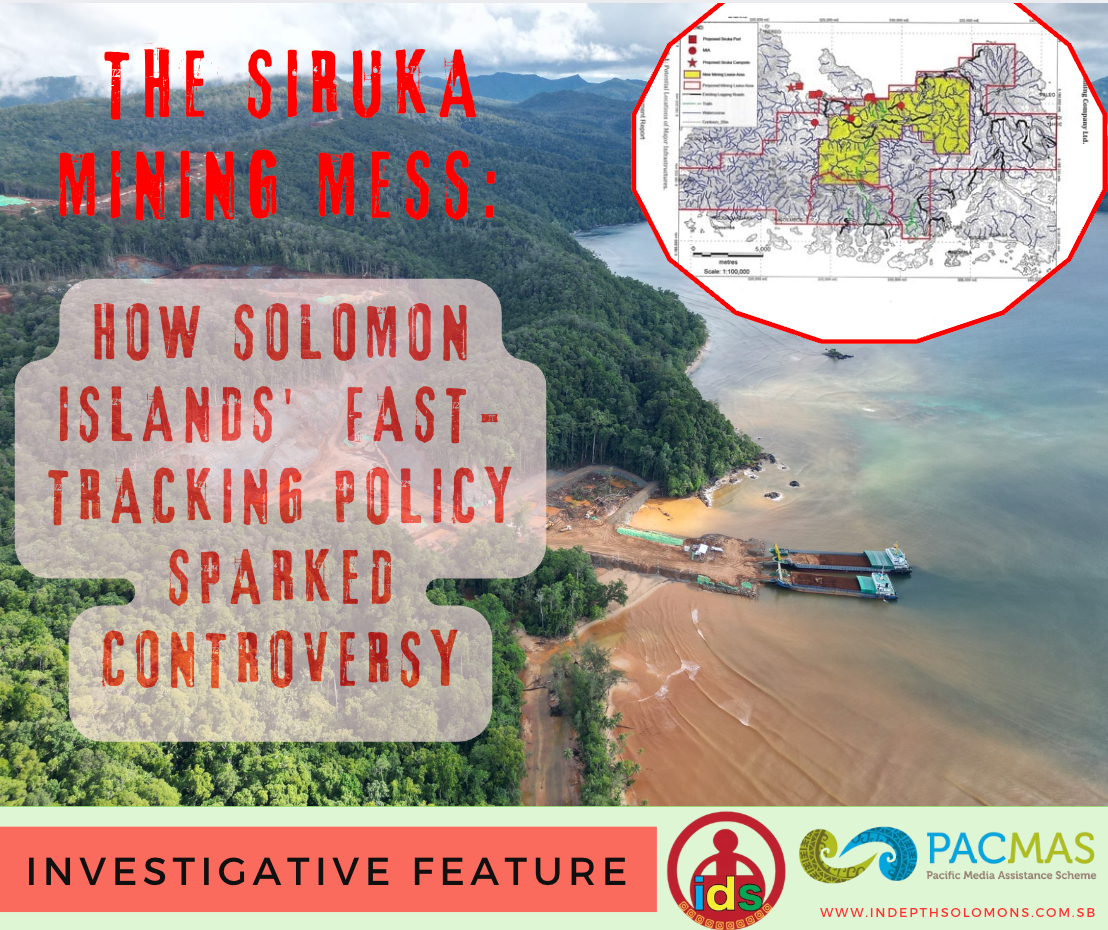

But in the fog-covered mountains of Siruka, in Sogavare’s own constituency of North East Choiseul, the policy has produced more controversy than recovery. A mining project has instead triggered allegations of environmental breaches, illegal operations, land disputes, and political favoritism.

Siruka Nickel Mining, operated by the newly incorporated Solomon Nickel Mining Company Ltd (SNMCL), owned by a well-known Filipino logger, Johnny Sy, is one of three projects pushed through under the “fast-track policy”, introduced and approved by cabinet in 2020 as part of a post-pandemic economic stimulus plan.

Two other fast-tracking projects in Isabel raise questions. The first is Solomon Islands Resources Company Ltd, operating in Suma. It is owned by controversial miner Dan Shi whose company, Win Win Investment Solomon Ltd, was accused of Gold Smuggling and compliance issues.

Another, Pacific Nickel Mines Kolosori Ltd, is currently operating at Havihau, Isabel Province.

Mines Director Krista Tatapu explained, “DCGA decided to fast-track three projects near the mining stages. Cabinet endorsed two in Isabel Province and one in Choiseul.”

But former Mines Director Nicholas Biliki insists the policy is nothing short of a political smokescreen.

Biliki claims he was removed from office for opposing questionable mining practices by local companies, including Shi’s Win Win.

“It’s a fake policy,” Biliki said.

“The pandemic became an excuse to waive legal processes. These newcomers are loggers who have no technical capacity to meet the best mining standards.”

In 2020, Solomon Islands Mining Limited, also owned by investor and logger Johnny Sy, started doing prospecting work at Siruka. His other company, SNMCL, took on and was granted a 25-year mining lease in November 2023, being incorporated in March the same year.

Environmental Red Flags and Official Inaction

Fresh concerns are now surfacing over the environmental impact of the Siruka operation.

A recent report by Transparency Solomon Islands (TSI) reveals serious environmental compliance breaches at the mine, including the company’s failure to install sediment-control barriers, a direct violation of the Environmental Impact Assessment Report (EIAR) requirements.

In-depth Solomons has recently visited the site to see TSI finding claims on the ground.

Ministry of Environment Director Joseph Hurutarau confirmed the violations, acknowledging that the company is in breach of environmental law.

“The company has not complied with environmental laws. We’ve warned them. But with limited resources, our office has yet to visit, verify, and enforce compliance,” Hurutarau said.

He said these breaches are not minor oversights.

“Sediment-laden runoff from mining threatens fragile marine ecosystems downstream, including the distant Waghena’s lucrative seaweed farms, which generate thousands of dollars annually for local communities.”

For critics, the case highlights the structural weakness of Solomon Islands’ environmental safeguards.

Veteran activist Lawrence Makili was blunt.

“It’s a shame the government keeps pushing large-scale mining operations without the resources and manpower to monitor the environmental damage, or the corruption, in the sector.”

Land Rights and Disputes, ‘We Were Never Consulted’

Siruka’s mining lease tenement covers a vast area stretching from Choiseul’s northern coast to its southern coast, encompassing lands whose traditional owners say they were never consulted.

The mapped lease areas cover disputed unacquired customary land areas where resource owners raise concerns about the legality of the operation.

One of them is Chief Zaxs Pui of the Kobongava tribe in South Choiseul.

He told reporters he was shocked to discover that his land had been included in the leased tenement without his knowledge or consent.

“Some of us are related to Bougainvilleans. We know the true cost of mining. We will do whatever it takes to protect our land,” Pui said, recalling the bloody civil strife relating to Bougainville’s embattled Panguna mine.

He accused the company of exploiting poverty and desperation among locals.

“They offered SBD1,000 to sign over land for mining. Many people signed without knowing the full implications. The miners are using some locals to go around with blank sheets of paper for people to sign up their land for only $1,000.”

Sy rejected the payment allegations as “False”. “I don’t need to pay anything because I already got the license to mine the area.”

Under the Mines and Minerals Act 1990, Section 33(1-6), a compulsory land acquisition process is required before mining leases can be granted.

Lands Commissioner Allan McNeil confirmed that “No land acquisition process was carried out at Siruka.”

Instead, the company relied on Surface Access Rights Agreements (SARA), a shortcut that bypasses formal acquisition and leaves ownership disputes unresolved.

Repeated attempts to obtain clarification from the Registrar General of the Lands Registry Office went unanswered, despite numerous visits and written questions submitted to his office for explanation as to why no land acquisition was done.

Johnny Sy dismissed the criticism, saying, “There’s no such requirement on that. Land acquisition is only to protect the investor, not a requirement for a mining lease,”.

He instead blamed the Ministry of Mines, claiming Director Krista Tatapu failed to act when his company requested land acquisition.

“It was the failure on her part and that of the government,” Sy insisted.

Tatapu, when contacted, replied, “Land acquisition processes take a lot of time”.

“Look at Gold Ridge, they haven’t completed the land acquisition process. There’s nothing in Choiseul and Isabel, too. We depend on the Surface Area Access Rights Agreement (SAARA) as land owners themselves agreed and signed up their lands for mining operations.”

Land-related issues can fester for years. For example, local landowners struggled for years against APID’s illegal land acquisition in West Rennell island, site of a bauxite mine.

The land was eventually returned to them, and in 2023, lands acquisition officer Penrose Palmer was convicted of corruption and fined $600 for his role in what the courts ruled was an illegal process.

Governance Breakdown at the Provincial Level

Choiseul Provincial Premier Harisson Pitakaka admits his government has been forced into a largely “passive role,” pressured to issue a six-month provincial business license to the Siruka operation, a license that has since expired.

“The company is operating illegally on an expired provincial license,” Pitakaka told In-depth Solomons.

“The government negotiated with us to give them an additional six months,” he said.

“We gave them all this year, with an assurance that the new bill will go before parliament, and the Provincial Implementation Agreement will be elevated from just being a policy to legislation.

“If the government and investors don’t play their part, we will eventually suspend the whole operation.”

He described the approval process as “rushed and heavy-handed”.

“To be honest, even when they pressured us, they rushed everything; their machines landed, and they only forced us to respond to the license. That gave us only a narrow gate to see clearly how we should respond, or what we expected.”

Pitakaka warned that the existing Mines and Mineral Act is doing an injustice to people.

“To say that 6 feet below the land surface is owned by the state must be changed in the new bill. It is people’s resources. It’s a law from the colonial masters.”

His predecessor, former Premier Tongoua Tabe, who was ousted after opposing both the Siruka project and another proposed bauxite mine on Wagina, said Solomon Islands is not ready for mining yet.

“Our mining laws are weak. Without reform, we cannot protect resource owners, governments, or the environment,” Tabe told In-depth Solomons.

“We are already feeling its impacts here,” he added.

Leader of the Opposition, Mathew Wale this week raised the same issue during the Bill and Legislation Committee.

“I am totally disappointed that during your consultations, you seemed not to discuss this 6 feet rule and included it in the new bill,” Wale challenged officials from the mines ministry.

“I know people are not happy with this. It’s the People’s resources. This has to be changed,” he said.

However, Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Mines Dr Chris Vehe, while acknowledging these concerns, said the current law considers it a costly exercise to compile a mining directory with resource owners who will not bear the costs incurred in the process.

“The 6 feet principle is therefore a fair distribution of wealth to resource owners and the people of Solomon Islands,” Vehe said.

The controversy deepened with revelations that the Siruka lease was among projects fast-tracked and granted by DCGA minister Bradley Tovosia during his tenure as Minister for Mines.

Critics, including Opposition Leader Matthew Wale, argue the approval was unprocedural, since under the law it is the Mines and Minerals Board, not the minister, that is empowered to approve mining leases.

Community Voices: Fear of environmental disaster

For coastal communities like Wagina, the environmental stakes are existential. The eastern tip of Choiseul is a place where the majority of the population depends on the sea for livelihood.

“Mining will destroy our marine resources forever,” said a youth leader, Norel Frances, from Taora, Rob Roy Passage.

“We earn SBD10,000 a month from seaweed. Those who signed up for mining are still waiting for royalties,” he added.

Chief Robertson Polosokia of Mamaka Tribe, who recently signed up his land for mining, now regrets the decision.

“We only had one meeting. No proper environmental safeguards have been followed. But it’s too late now, I’ve signed up already, and the operations are underway in our lands.”

Elder Elwin Pitakoe of Toara warns of a Bougainville-style crisis if grievances are ignored.

“In Bougainville, landowners got nothing,” Pitakoe said, referring to the Panguna copper and gold mine that sparked a civil war in 1998 and claimed more than 15,000 lives.

“Land issues here are just as unresolved. My fear is young people taking up law into their own hands. We elders think the operations should be put on hold for now so we can settle land issues here first,” he added.

Ronald Lapo, one of the land owners and land trustee in South Choiseul, said the majority of people in the Southern Region are not happy with the operation.

“We depend very much on marine resources, and this operation is simply a disaster. Those Trustees are not representing our people; they are a few hand-picked individuals who can be easily manipulated by money.”

“We have seaweed farmers from here down to Waghena, and definitely, impacts from these mining operations will have an adverse effect on our seaweed farmers. The worst case is that the government miserably failed us; despite what they said, it’s their fast-tracking policy. This operation must stop!”

Ronald Lapo, Land trustee, South Choiseul.

He added, “Our land is so small, but my brothers and uncles have signed up already. Instead of coming to talk with us openly, they took the trustees to sign up our lands behind closed doors. There’s no transparency with these so-called investors. The whole tribe did not know about their deals. No consultations have been done with the majority of our people.”

The Players Behind the Project

Solomon Nickel Mining Company Ltd is owned by businessman Johnny Sy, a prominent figure in Solomon Islands’ logging industry and president of the controversial Solomon Forest Association (SFA).

Sy previously operated logging concessions in East Choiseul. He incorporated SNMCL in March 2023, despite claiming to have done prospecting since 2018.

Sy currently rents an apartment owned by the former Prime Minister Sogavare at Lounga, East Honiara and reportedly enjoys strong connections in government circles.

The mining lease was granted by then-Minister of Mines Bradley Tovosia, and has been the centre of mining controversy by issuing licences without the Mines and Minerals Board, a body set up to oversee mining licenses and leases in the country.

Mr. Sy supported Sogavare’s electoral victory in the last election.

SNMCL former employee, Mendana Doleveke, said, “We were working on surveying the land for mining, and then we had the election going on too. So our salary was on hold for a month. Our Boss, Mr. Sy, told us that he is helping our MP Sogavare to win the election. He asked us to be patient after the MP wins the elections, we will have our pay later”.

Asked if there are possible conflicts of interest in these operations and a close relationship with Sogavare, Mr. Sy said, “Anyone can rent his house. No strings attached.” He added, “I am a Solomon Islander. It’s the right of every citizen to choose who they support. But in terms of funds, it’s nothing! Property rental in Sogavare’s building is his own business, and we don’t have the right to tell him if he used the fund for election or not; it’s his own money we paid.”

Transparency Solomon’s CEO Ruth Liloqula said, “I was at home during the election period. I have seen and heard that Mr. Sy’s vessels are transporting voters from Honiara to Sogavare’s constituency. Nothing is hidden. Not only Sogavare, other MPs in Choiseul, too, especially those in the government!”

But Mr Sy denies the allegations.

Mr Sy is the current President of the Solomon Forests Association. Besides Solomon Nickel Mining Company Limited, Sy is a director/shareholder of several companies, including:

- Bulacana Integrated Woods Industry (SI) Co. Ltd -Director

- Solomon Islands Mining Company Ltd – Director

- South Pacific Mining Company Ltd- Director/Shareholder

- Filsol Shipping Company Ltd – Shareholder/Director

- Sea Links Agency Ltd – Director

- Best Food Manufacturing (SI) Company Ltd- Director

- Solomon Sawmill United Ltd – Director

- Winlex Trading (SI) Ltd -Director/Shareholder

- Best Foods Manufacturing (SI) Company Ltd – Director/Shareholder

- Winlex International (SI) Company Ltd -Director/Shareholder

Shipments, Royalties, and Secrecy

Since operations began, five shipments of nickel ore have left Siruka, with at least four more in loading stages. The first shipment suffered a liquefaction incident en route to China and was diverted to Indonesia earlier this year.

Some landowners say they were told royalties would not be paid until three years after operations began, far longer than the 90 days stipulated under mining regulations.

Chief Robertson said, “On Siruka’s side, they have been mined, and they were promised to get our royalties after 3 years.”

But Mr. Sy confirmed, “Five shipments have been left so far.” He claimed, “We have paid royalties for all the shipments.”

Mines Director Tatapu assured resource owners that the royalty payment for the first shipment only is underway and will soon be released to landowners.

Siruka Mining Project Community Relations Officer Humphrey Henry Kimasaru said, “The royalties have to go through the central government before being released to resource owners. Shipments have left, and no royalties as yet. I am currently being pressured by resource owners about their royalties.”

He added, the mining operation has already created more than 400 job opportunities for locals.

A Pattern of Broken Promises

For TSI and other watchdogs, Siruka’s situation is alarmingly similar to the Rennell Island mining scandal, which left environmental devastation and minimal community benefit of its 33 unpaid mineral shipments to date.

“It’s the same story from Rennel, the government and its cronies profit while poor people suffer,” TSI’s CEO Ruth Liloqula said. “It’s a complete mess.”

With no completed land acquisition, no independent environmental assessment and monitoring, and an expired provincial business license, the Siruka mine stands as a test case for Solomon Islands’ mining future. And whether fast-tracking policy serves the public good or private interests, it is what it is now. Mining activities continue.

What is at stake now are not just the nickel deposits buried in Choiseul’s soil, but the community’s trust in the government and the law, as well as the survival of marine and forest ecosystems that sustain life far beyond the mine’s boundaries.

“This story was produced with funding support from the Pacific Media Assistance Scheme PACMAS.”