by Stephen Howes and Richard Curtain

Kirstie Petrou and John Connell’s new book Pacific Islands Guestworkers in Australia: The New Blackbirds? is an important publication.

It is the first book on the Seasonal Worker Programme (SWP) – now part of the broader Pacific Australia Labour Mobility or PALM scheme – which, since 2007, has allowed Pacific Islanders to work on Australian farms.

It is an interesting read, but a flawed account.

In the first five chapters the book moves through the history of migration from the Pacific to Australia.

Chapters 6 to 9 are on seasonal workers’ experiences, often negative, in Australia and on returning home.

Chapter 10 is on COVID-19, chapter 11 on the comparison with blackbirding, and chapter 12 concludes.

From chapter 5 onwards, the book has a strong focus on Vanuatu with some reference to other Pacific countries.

Timor-Leste receives very little attention, despite its third-place ranking in the number of seasonal workers sent.

Overall, the authors have a positive view of the SWP. They say that it “appears to be a triple win” (p. 416) – good for employers, workers, and their countries.

They write that “on balance, the SWP benefits most people most of the time” (p. 413).

Nevertheless, despite this summary positive verdict, the book has quite a negative tone. This is for five reasons.

First, the authors’ style is ambivalent, and they distance themselves from their own positive verdict.

The concluding paragraph of the book summarises the SWP not in the positive terms quoted above but as “asymmetrical, ephemeral and occasionally exploitative” (p. 449).

Second, the authors frame the SWP as a cheap source of labour for agricultural employers (p. 104).

In fact, SWP workers are paid on casual rates which are 25% above the minimum wage.

The range of other costs and obligations incurred by approved employers, such as providing welfare support for the workers, makes an SWP worker an expensive employment option.

Research in 2018 showed that non-wage costs per hour were higher for seasonal workers than for backpackers.

Many growers still prefer lower cost backpackers, international students, undocumented workers and absconding SWP workers.

Third, the focus in the chapters on SWP workers in Australia is on the problems they have faced. The analysis is too reliant on anecdotes.

The reader is presented with a series of snapshots at different times and places, at different stages of evolution of the SWP, and indeed from other seasonal work programs in other countries.

It is often a confusing picture that emerges.

For all the material that is presented, Petrou and Connell cannot address the issue of how well or badly Pacific seasonal workers are treated.

They offer at the beginning of chapter 7 this disclaimer: “we emphasise the impossibility of quantifying the extent of the issues discussed here; many guestworkers experienced no serious problems during their stay in Australia and most wanted to return again” (p. 188).

Fourth, the two authors dismiss seasonal work as something that doesn’t “contribute significantly to long-term development or … triumph the poor as agents of their own development” (p. 418).

This is very odd, especially since the authors admit that “in small island states choices are truncated” and “a poverty of opportunity prevails” (p. 416).

Richard and Charlotte Bedford’s research on New Zealand’s equivalent scheme, the RSE, shows that more than one in every five Samoan and ni-Vanuatu men aged 20-49 years have been an RSE worker at some point since 2007.

For Tonga, the ratio is one-third. Any suggestion that this mass movement of people is not the poor acting as agents of their own development (literally, voting with their feet) is bizarre.

We don’t have equivalent figures for Australia’s SWP but the program is now bigger than New Zealand’s RSE.

In other research, we have shown that employment on the SWP and RSE combined is now comparable with government employment in Samoa, Tonga and Vanuatu.

Yes, remittances have not made any country rich. But if the SWP isn’t a significant contribution to long-term development, we don’t know what is.

Fifth, the authors fail to give a clear answer to their title question.

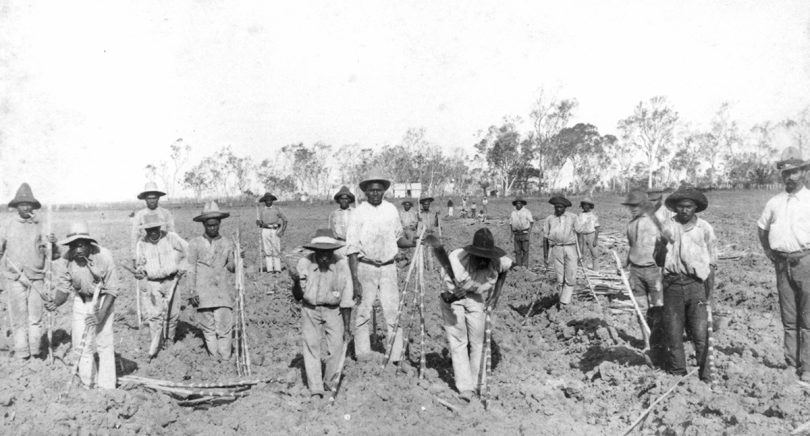

Blackbirding was the mass recruitment of Pacific Islanders to work on plantations in Australia and elsewhere in the late nineteenth century, a practice that, as the authors write, “combined some degree of economic necessity at home and coercion and incentives from recruiters” (p. 47).

At one point, the authors say it is “remarkable … how similar” the SWP is to blackbirding (p. 53).

This leads one to think that their answer is yes, SWP workers are the new blackbirds.

On the other hand, later in the book, the authors talk about both the “obvious differences” and the “intriguing parallels” (p. 386) between the SWP and blackbirding.

However, they mention only two differences: that “no workers now migrate against their will and contact with home is usually easy enough”. Two other critical differences are not mentioned.

One is all the safeguards embedded into the SWP to prevent exploitation, including that participating employers have to be licensed and agree to numerous conditions, from the provision of regulated accommodation to the delivery of pastoral care; that unions are notified when workers arrive; that Pacific workers have to be paid exactly the same as Australian ones; and so on.

It is this high degree of regulation that explains why research has found that SWP workers fare not worse but better than other horticultural employees.

A 2017 report by Adelaide University academics found that “The SWP results in less exploitation of workers.”

That report continues: “The design of the SWP means that less incidents of worker exploitation have emerged when compared with other low-skilled visa pathways [e.g., backpackers].”

The other obvious difference between blackbirding and the SWP is that Pacific workers were ingloriously deported from Australia due to the introduction of the White Australia policy and the Pacific Island Labourers Act of 1901.

In contrast, the SWP is here to stay. The extent of its growth post-COVID is uncertain and, eventually, demand for farm work may fall victim to automation, but that is only in the very long term.

Already Pacific farm workers can stay for up to four years if they can find an employer willing to sponsor them, and the Pacific Engagement Visa will allow those SWP workers lucky enough to win the lottery the right to stay in Australia as permanent residents.

Are SWP workers the new blackbirds?

No. Clearly, the “obvious differences” outweigh the “intriguing parallels”.

But you won’t find that out by reading Petrou and Connell’s interesting but ultimately obfuscatory book.

* This article appeared first on Devpolicy Blog (devpolicy.org), from the Development Policy Centre at The Australian National University. Stephen Howes is Director of the Development Policy Centre and Professor of Economics at the Crawford School of Public Policy, at The Australian National University.

Richard Curtain is a research associate, and recent former research fellow, with the Development Policy Centre. He is an expert on Pacific labour markets and migration.